Photo: Joods Historisch Museum via Wikimedia

On 7th September 1943, a year after writing the following diary entry, 29-year-old Etty Hillesum and her family were sent from Westerbork transit camp to Auschwitz, where she would meet her tragic end two months later. Born in 1914 in the Netherlands, Hillesum was a woman of keen intellect, initially drawn to studying law, Slavic languages, and psychology. Yet, as the shadow of the Holocaust darkened, aware that she could soon be facing a similar end, Hillesum chose to volunteer at Westerbork, offering emotional support to Jewish detainees awaiting their terrible fate. The Klaas to whom she speaks in this entry is friend and fellow writer Klaas Smelik, the person tasked with ensuring that Hillesum’s diaries were published after her death.

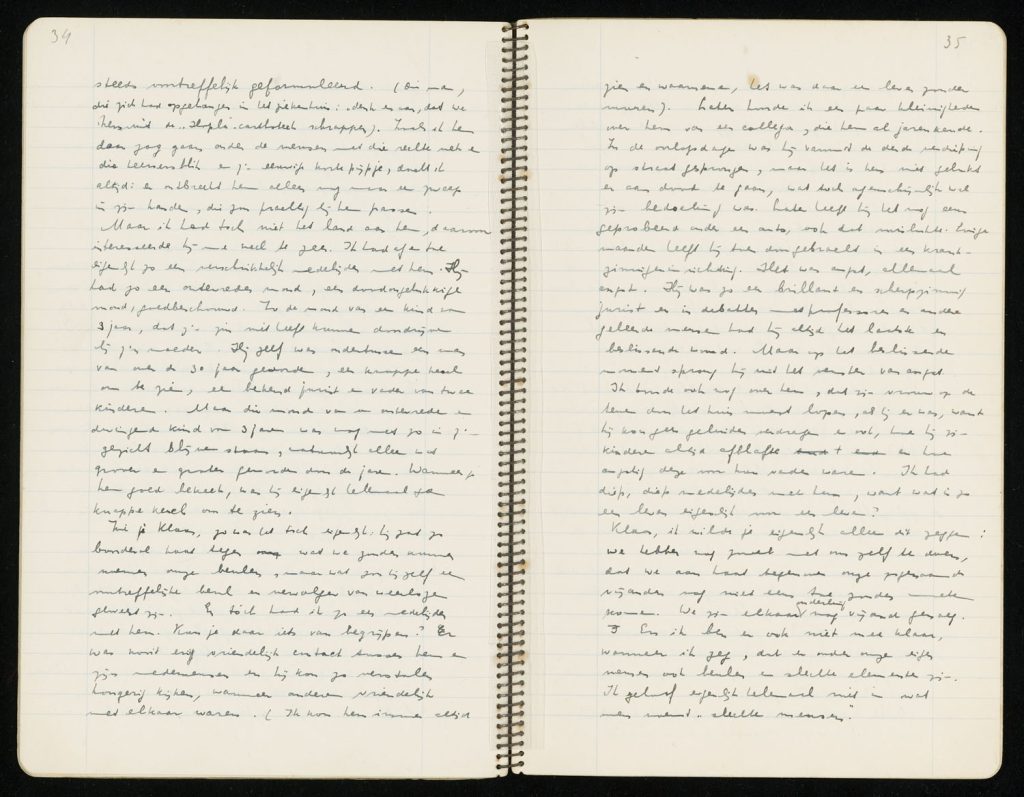

The Diary Entry

Image: Joods Historisch Museum via Het Geheugen

23 September

We shan’t get anywhere with hatred, Klaas. Appearances are so often deceptive. Take one of my colleagues. I see him often in my thoughts. The most striking thing about him is his inflexible, rigid neck. He hates our persecutors with an undying hatred, presumably with good reason. But he himself is a bully. He would make a model concentration camp guard. I often watched him standing beside the camp entrance to admit his hunted fellow Jews, never a pleasant sight. I also remember his throwing a few grubby pieces of licorice to a sobbing three-year-old across the table and saying gruffly, “See you don’t get it all over your face.” Thinking back, I’m sure it was more awkwardness and shyness than lack of goodwill that made him seem curt—he simply couldn’t hit the right tone. When I saw him walking about among the others with his rigid neck and imperious look and his ever-present short pipe, I always thought, All he needs is a whip in his hand, it would suit him to perfection. But still I never hated him, I found him much too fascinating for that. Now and then I really felt terribly sorry for him. He had such an unhappy, miserable mouth, if the truth be told. The mouth of a three-year-old who has been unable to get his way with his mother. He himself had meanwhile passed the thirty-year mark, a clever fellow, a successful lawyer—one of the most able in Holland—and the father of two children. But the mouth of a dissatisfied three-year-old had been stamped on his face. There was never any real contact between him and others, and he would give such covert, hungry looks whenever other people were friendly to each other. (I could always see him do it, for we lived a life without walls there.) Later I heard a few things about him from a colleague who had known him for years. During the German invasion he jumped into the street from a third-floor window but failed to kill himself. Later, he threw himself under a car, but again to no avail. He then spent a few months in a mental institution. It was fear, just fear. I also learned that his wife had had to walk on tiptoe in the house because he could not bear the slightest noise and that he used to storm at his terrified children. I felt such deep, deep pity for him. What sort of life was that? In the end he hanged himself. (I must make sure his name is taken off the card index.)

Klaas, all I really wanted to say is this: we have so much work to do on ourselves that we shouldn’t even be thinking of hating our so-called enemies. We are hurtful enough to one another as it is. And I don’t really know what I mean when I say that there are bullies and bad characters among our own people, for no one is really “bad” deep down. I should have liked to reach out to that man with all his fears, I should have liked to trace the source of his panic, to drive him ever deeper into himself, that is the only thing we can do, Klaas, in times like these.

And you, Klaas, give a tired and despondent wave and say, “But what you propose to do takes such a long time, and we don’t really have all that much time, do we?” And I reply, “What you want is something people have been trying to get for the last two thousand years, and for many more thousand years before that, in fact, ever since mankind has existed on earth.” “And what do you think the result has been, if I may ask?” you say.

And I repeat with the same old passion, although I am gradually beginning to think that I am being tiresome, “It is the only thing we can do, Klaas, I see no alternative, each of us must turn inward and destroy in himself all that he thinks he ought to destroy in others. And remember that every atom of hate we add to this world makes it still more inhospitable.”

And you, Klaas, dogged old class fighter that you have always been, dismayed and astonished at the same time, say, “But that—that is nothing but Christianity!”

And I, amused by your confusion, retort quite coolly, “Yes, Christianity, and why ever not?”

At night the barracks sometimes lay in the moonlight, made out of silver and eternity: like a plaything that had slipped from God’s preoccupied hand.

Further Reading

Etty Hillesum’s beautifully written diaries from this period filled eight notebooks, all of which eventually found their way to Klaas Smelik. It would be another forty years until those diaries made it to print, in a book titled Het verstoorde leven (‘An Interrupted Life’). Her diaries and letters have since been translated into eighteen languages, including in English bearing the title, Etty Hillesum: An Interrupted Life: The Diaries, 1941-1943; and, Letters From Westerbork.

Also…

- Etty Hillesum’s original handwritten diaries can be seen on the Het Geheugen website

- Etty Hillesum at Wikipedia

- The website of the Etty Hillesum Research Center

Diary entry excerpted from Etty Hillesum: An Interrupted Life: The Diaries, 1941-1943; and, Letters From Westerbork. Translated from the Dutch by Arnold J. Pomerans. Reprinted by permission of Picador, an imprint of Macmillan Publishers. Translation Copyright © 1983 by Jonathan Cape Ltd.

Leave a Reply